The Other Place - A Review

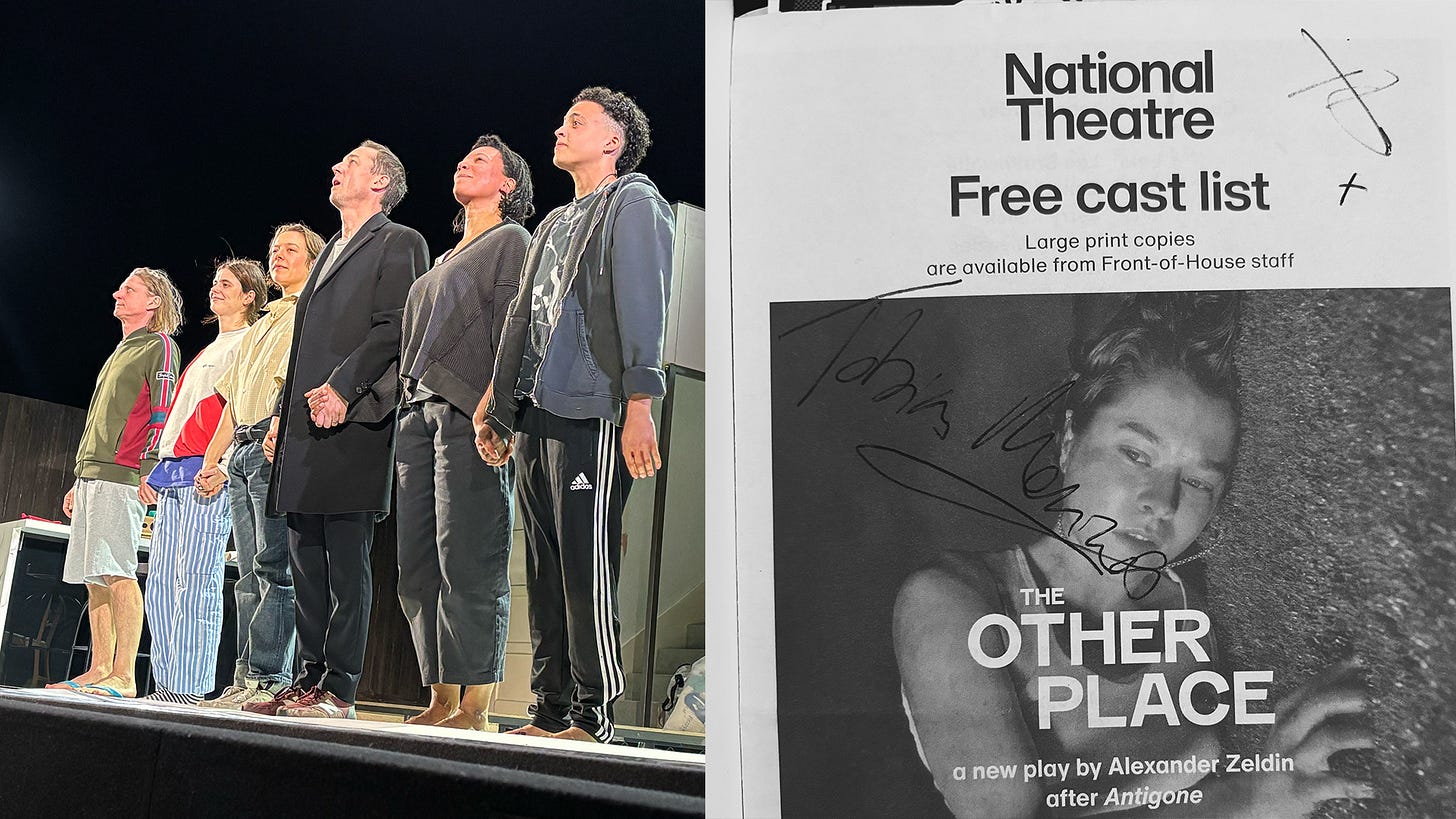

From the National Theatre, a theatre newbie's review. Watch this play on National Theatre at Home in March.

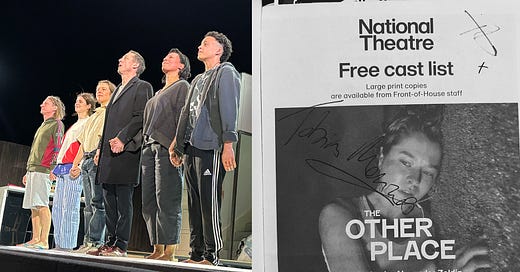

Attending The Other Place at the National Theatre’s Lyttelton Theatre in October 2024 was not just my first experience with London theatre; it was my first experience with theatre, period.

It was also my first trip to the United Kingdom.

This performance left a profound mark on me. I was drawn to the initial premise of the displaced, angry daughter coming home after a long absence. This is a theme that hits far too close to home, as prior to visiting London, I visited the U.S. after many years away, visiting family that largely see me as the black sheep, the problem child, the one nobody calls unless there’s a problem that can be blamed on me. A return where many things were different, awkward, and uncomfortable.

So the initial themes I took from the promos resonated deeply.

Written and directed by Alexander Zeldin, the play stars Emma D’Arcy in a raw and devastating performance. It also stars Tobias Menzies, Alison Oliver, Nina Sosanya, Jerry Killick, and Lee Braithwaite.

The play is a contemporary reimagining of Antigone, Sophocles's ancient Greek tragedy. In Antigone, the titular character defies the law to properly bury her brother, who the state has deemed a traitor. Her refusal to comply leads to tragic consequences, as she is punished for honouring the dead. The play has been interpreted in many ways—as a story of rebellion, morality, duty, and the cost of defying power.

But when I walked into The Other Place, I knew nothing about Antigone. I had no prior knowledge of its themes, characters or legacy. So I could not, and still do not, draw any direct comparisons or see the ways in which this play echoes the original.

Instead, I experienced this play with fresh eyes brand new to the theatre — I mean, come on, if you’re going to visit London, not experiencing the theatre is a crime. Why go?

This review is my interpretation — not a scholarly analysis by a professional critic knowledgeable in the classics.

At its core, The Other Place is a story of homecoming — but not in the way we long for. Rather, a daughter returns to a home that is no longer hers, a family that no longer feels like hers, and a past that refuses to stay buried. What follows is a masterfully written and very unsettling exploration of grief, trauma, and estrangement. Every conversation is fraught with subtext, every silence loaded with what nobody dares to say aloud or give life to.

Emma D’Arcy delivers a defining performance that is both fierce and fragile, carrying Annie’s grief, rage, and disillusionment like a second skin.

Tobias Menzies is deeply unsettling as Chris, a man who wields power not through violence but through quiet, insidious control.

Nina Sosanya and Alison Oliver bring complexity to their roles, portraying the nuanced ways women are pressured into complicity—whether through fear, denial, exhaustion, or the weight of subtle societal conditioning.

Jerry Killick’s portrayal of Terry, a family friend whose casual cruelty makes your skin crawl, adds yet another layer of unease. There is something terrifyingly familiar about him—the kind of man who laughs at the suffering of others, who reinforces abuse with an offhand remark, who makes looking the other way feel normal.

Lee Braithwaite, as Erica’s teenage child Leni, is the only true innocent in the play. There is a heartbreaking contrast between Leni’s quiet sincerity and the suffocating darkness of the household. They’re the only one who seems to try and see Annie for who she might be, rather than who others say she is. But that isn’t enough.

This play was not entirely easy to watch, and I cried more than once during the hour-and-a-half (roughly) show. It does not give the audience relief or closure; instead, it forces us to sit with discomfort.

Something I’d like to point out before I continue was that at the conclusion of the show, as we were all filing out of the theatre, I listened to a number of people around me complain that they didn’t understand the show and how it didn’t make sense, yet I feel like I understood the show perhaps in a way that was not intended based on its pull from Antigone.

It’s entirely possible I took from this show a non-intended view and conclusion.

The Story (Spoilers Ahead)

Annie (Emma D’Arcy) returns to her childhood home after years away, but it is no longer hers.

Her father is dead. Her uncle, Chris (Tobias Menzies), has inherited everything—the house, the money, the authority. He is in the process of gutting the home, stripping it of its past and making it unrecognizable.

His new wife, Erica (Nina Sosanya), now occupies the space alongside her teenage child, Leni (Lee Braithwaite). Annie’s sister, Issy (Alison Oliver), still lives there, but the bond they once shared has withered, reduced to something polite and distant.

The reason for Annie’s return? To scatter her father’s ashes.

But from the moment she steps inside, the tension is unbearable.

No one quite knows how to talk to Annie, and she doesn’t know how to talk to them. She moves through the house as if it is a crime scene, each missing object another piece of her childhood erased. Even the trees in the backyard—the ones her father hanged himself from when she was sixteen—are set to be cut down.

Chris treats her with a strange mix of forced kindness and dismissive authority. He insists that scattering the ashes is the right thing to do and that keeping them in the house is unhealthy.

It is easy to see how he has rewritten history in his own mind—how he has convinced himself that he is the one making logical decisions, while Annie is simply being difficult in her unwillingness to spread the ashes.

Issy doesn’t seem to have strong feelings either way. She was younger when their father died—too young to fully grasp the extent of his struggles. The way the others speak about him paints a picture of a man who was unpredictable and troubled—someone who would shout at birds, disappear into himself, and exist in a world only he understood. It’s clear, in pieces, that he suffered from some kind of mental illness.

But Annie remembers him differently.

As the eldest, she was the one who carried the weight of understanding him. She learned how to read his moods, how to handle him, and how to soften the edges of his volatility. She was never meant to be his caretaker, yet she had taken on that role in ways she could never articulate and most likely never truly realised or understood.

Now, she is the only one left who still clings to the memories of who he was—not just the man who struggled, but the father she loved. Mixed with these feelings are feelings and memories of something far more sinister and traumatising, whether she realises it or not.

And then there’s Terry (Jerry Killick)—a contractor, an old friend of Chris’s, a man who lingers around the edges of conversations with the unsettling ease of someone who has always been a little too comfortable in his cruelty.

He talks about Annie’s father with open mockery, calling him crazy and unstable. He speaks about Annie in the same way.

“She’s just like him.”

With those words, the gaslighting begins.

It is a slow, insidious dismantling of Annie’s reality—the quiet but deliberate suggestion that her grief is irrational, her attachment to the past unhealthy, and her emotions unstable.

And this is how abuse is erased—not with overt violence, but with dismissal, with laughter, with an entire room subtly agreeing that the problem is not what happened, but the fact that she refuses to move on.

A Slow Collapse

Unable or unwilling to sleep in the house, Annie pitches a tent in the backyard, but not just any tent.

Her father’s tent.

The same tent, it’s revealed, that she and her uncle Chris slept in together in the nights following her father’s suicide. Pitched in front of the trees he hung himself from “with a smile on his face.”

And now she returns to this same spot, in the same tent.

It is perhaps an unconscious return to something buried in her memory, an attempt to understand something that she subconsciously knows is wrong but consciously is utterly confused about.

It is revealed later in the play that when they camped in the tent together following this tragedy, that it was more than an uncle consoling a niece. He told her she was special. He told her she was the only one who understood him. He promised her he’d keep her father’s ashes in the house. He promised to take care of her and her sister. He groomed her. He took advantage of her.

Annie didn’t, and doesn’t, see or understand this as abuse. She believes she had something real with him.

But then he moves to get rid of her.

He sends her to a school far away. Pushes her out of her home and out of his life. Tries to buy her off with money as he paints himself as the doting uncle, only trying to do the best for his brother’s child and willing to give her whatever she needs financially.

It’s said in the play that Chris had a great smile on his face when he found out his brother was dead. Was he happy that he no longer had to deal with his unwell brother, or happy that he was the sole inheritor of his brother’s estate?

Since he owns the home, instead of the girls, I believe it’s the latter.

As she moves through the house, Annie then drapes herself in her father’s old clothes. Clothes that were piled up to be disposed of as they cleaned out the house — further erasing what was left of her father. She agonises to Chris that he promised to keep the ashes in the home, and he dismisses her once again.

In a quick act, while the house is empty, Annie empties her father’s ashes into a bag, hides them in her baggy clothes, and leaves the urn. Upon their return, she relents in the overarching argument surrounding whether or not to spread the ashes and tells them she’s changed her mind and to go. A notion Chris gladly accepts.

It’s not long, of course, before Chris realises what’s happened and returns to the home furious.

He digs through Annie’s backpack that she’s been living out of, noting her containers of rotten food, which speak to her depression and struggle but are instead used to paint Annie in a dark light.

He then makes no hesitation to put his hands on Annie, wrestle her to the floor, and put his hands down her pants in search of the ashes. It was during this scene that I believe we, as the audience, received the first inkling of what Chris may have done in the past — at least I did.

It is after this incident when Chris and Annie are later alone, that what happened in the tent truly comes to light, as Chris drapes a cloth over his face and proceeds to relive the childish scenario he displayed in her youth, as he tells her that she is still the only one to ever see and understand him.

It’s an unsettling scene, made more so as Annie reciprocates and meets him beneath the cloth, initiating a kiss that truly and without question reveals what happened in that tent years before.

The weight of this realisation was suffocating. I feel, that while Annie still consciously believes she has some kind of connection with Chris, as he groomed her to believe, that her initiation is an unconscious reenactment of a wound that never healed, was never understood, and remains open and raw.

Unfortunately, Erica walks in on them and ultimately does nothing. She retreats after witnessing this deep interaction between Chris and Annie.

Instead of confronting what she has seen, she pretends it didn’t happen. She later returns and continues about her business, chattering about the renovation and housework, and diverts her attention to anything other than what she walked in on earlier.

Because if she admits what she witnessed, she will have to acknowledge the man she married.

Chris moves to hide behind whatever pillar or wall he can find, peering around each corner in fear of what may happen, because while Erica has thus far refused to acknowledge what has happened, he knows exactly what he’s done.

Later, when the truth can no longer be ignored, Erica finally speaks, nearly in hysterics, as she tries to communicate to Issy what has happened between Chris and Annie, she does so not in a way that defends Annie, the child obviously groomed by an adult man, but in a way that paints them as lovers. Cheaters. She paints Annie as the one who is inappropriate and does not, in any way, acknowledge the true depth of depravity on her husband’s part.

Even Annie’s sister, the one person who should have been on her side, turns against her. Rather than recognizing Annie as someone who was hurt and cast aside, Issy blames her. She calls her dramatic, attention-seeking. She does what so many people do when confronted with abuse they don’t want to face: she makes it the victim’s fault.

This is what makes Annie’s final act so inevitable, so painful. This is how Annie’s story is rewritten in real time by her family.

She has spent years trying to outrun what happened to her. Trying to exist in a world that has already written her off. Trying to make peace with a family that refuses to see her pain for what it is.

And when she realizes that nothing will ever change—that Chris will never face consequences, that her family will never acknowledge the truth that her subconscious is striving for, that she will always be seen as the broken one—she makes the only choice she believes she has left.

She returns to the tent.

To the place where she was groomed. To the place where she was hurt. To the place where she was told she was special, even as she was being destroyed.

And she never comes out.

It is young Leni, the innocent character removed from this family’s tangled history, an outsider by circumstance rather than choice, who shows any compassion for Annie. Throughout the play, Leni watches, listens, and senses the tension, but they don’t understand the gravity of what’s happening around them and look on with ignorant innocence.

So it is Leni alone who goes looking for Annie, who shows any compassion for this stranger in his home and returns with blood on his hands and profound shock on his face at what he finds.

In that instant, the only innocent person left in this household is forced to carry a weight they should never have had to experience, let alone bear.

Annie is dead, yet the story will never be told that way. It won’t be framed as the story of an abused girl who was discarded by the people who should have protected her. It will not be a story about what was done to her, about how she was manipulated, gaslit, and ultimately erased. Instead, it will be about a troubled girl who was just like her troubled father.

Because that is how the world makes sense of tragedies like this.

It is easier to say that she was mentally unstable than to admit that she was a victim of abuse. It is easier to say that she was always difficult than to confront the fact that no one ever helped her.

Chris will survive this. Men like him always do.

The family will grieve her, but in the way people grieve someone they failed. There will be guilt, whispered regrets, and uncomfortable silences over dinner. But nothing will change.

Because this is how the world lets predators walk free.

This is how we fail young girls, over and over again.

And when they finally collapse under the weight of what was done to them, we do not ask, Who did this to her?

We ask, What was wrong with her?

And then we bury her.

For those who didn’t have the chance to see The Other Place live at The National Theatre in London, there’s good news—the production will be available to stream on National Theatre at Home starting March 20, 2025. This means everyone will have the chance to experience Alexander Zeldin’s gut-wrenching reinterpretation of Antigone, brought to life by an incredible cast:

• Emma D’Arcy as Annie

• Tobias Menzies as Chris

• Alison Oliver as Issy

• Nina Sosanya as Erica

• Jerry Killick as Terry

• Lee Braithwaite as Leni

(Check National Theatre at Home for availability, as streaming rights may vary by region.)